|

Answers provided by Director Nicholas Brown.

What inspired this story?

NB: This story was inspired by the book “The Serengeti Rules” by Sean Carroll, who had started his research after making a trip to the Serengeti and his kids asked him “how come this place has so much more wildlife than anywhere else?” He didn’t learn the answer until he started talking to the people this film is about. Describe some of the challenges while making this film. NB: The science behind the film is intensive, controversial and in many respects brand new, so we had to learn a lot about ecology in a short period of time. (In development we had three PhD’s on our research team). This is also a story with a lot of characters and storylines that cover the entire globe. The hardest part was deciding what not to film! We also were unconvinced there was a way to knit together all of these diverging threads in different ecosystems. In the end we narrowed it down to just 5 scientists and locations, and that is the story that emerges. How do you approach science storytelling? NB: We feel it is essential that audiences be given an emotional connection to the story, especially when the subject matter is as intellectual as this is. In this case we used dramatic reconstruction to draw people closer to the key characters. We hope that you, the viewer will fall in love with nature just as our characters did. We also feel the science is easier to comprehend if you have a fully rounded human being that you can identify with and follow through the story. We let our characters tell their personal journeys without resorting to narration. This unfiltered approach is a way of showing the audience respect, and trusting that they will figure out the difficult bits on their own. What impact do you hope this film will have? NB: In some ways the film is already having the impact we hoped for most, and that is inspiring younger people—especially those aged 10- 21—to fall in love with ecology. Biodiversity loss and extinction are depressing issues, so it is important that we project a story that also has some hope. We notice that young audiences are really latching onto this positive message. Ultimately, we hope that the science and the people will inspire everyone who watches the film. The best quotes-- and we’ve heard this more than once--come from 11 year olds saying, “When I grow up I want to be an ecologist!” Were there any surprising or meaningful moments/experiences you want to share? NB: Early in the process we knew we had to film the man who got this story going: Bob Paine. We’d set a date to make him the first person we would interview. But not long after agreeing a date, Bob called us to say that he was ill, but was still eager to take part in the film. Then, just a week before the interview, Bob’s daughter called to say he might not live to see the morning. We were shocked, and more than a little depressed. We cancelled our plans to film Bob, and were considering cancelling the whole film when Bob emailed. He said that he wanted to film with us no matter what. He wanted to get this story out there. On the day we arrived, Bob had just a matter of minutes per day where he was even awake and able to speak. He gave us 20 minutes per day on two consecutive days to interview him. Can you imagine, being on your deathbed, in agonizing pain, willing to talk to a film crew? You see, for Bob his work was so much more than a job. It was his passion and his mission, and he wanted to share what he had learned right up to his dying breath. He passed away less than a week after we finished the interview. The film is dedicated to his memory.

What next?

NB: The next step for us is to get this film distributed as widely as possible. We have plans to get it into schools and classrooms. And we hope to find distribution to the widest possible audience. Editing: What are the specific editing challenges you had to address? NB: We decided early on that we wanted the audience to have a direct cinematic experience, unfiltered by a narrator. This meant working with days if not weeks worth of interviews, and threading together a story that we hope people can follow with ease. Science, especially when it is new, is not always easy to explain or understand. Often there isn’t even a language for what you are trying to get across. We literally had to coin the term “upgrading” (instead of phrases like “trophic cascade restoration) to make the film understandable. Interestingly, the term “upgrading” is starting to crop amongst scientists now. Where there any unexpected surprises or breakthroughs during this film investigation? “The Serengeti Rules” is based on the book by Sean Carroll. At first glance, it was hard to see how this book—which journeys from molecular biology to medicine and finally to ecology—would make a film. Feature documentaries work best when they follow a single narrative thread—and better yet, a single character. Once we narrowed this story down to 5 scientists, we had the first glimpse that we might be able to tell this story with a film. What kept us going was the importance of the subject matter. The breakthroughs happened over the course of 50 years and 5 lifetimes of intensive study. Ultimately, the discovery these scientists made is profound, and it will change how conservation is done from now on.

1 Comment

Answers provided by Producer/Directors (or Filmmakers) Andrew Young and Susan Todd.

What inspired this story?

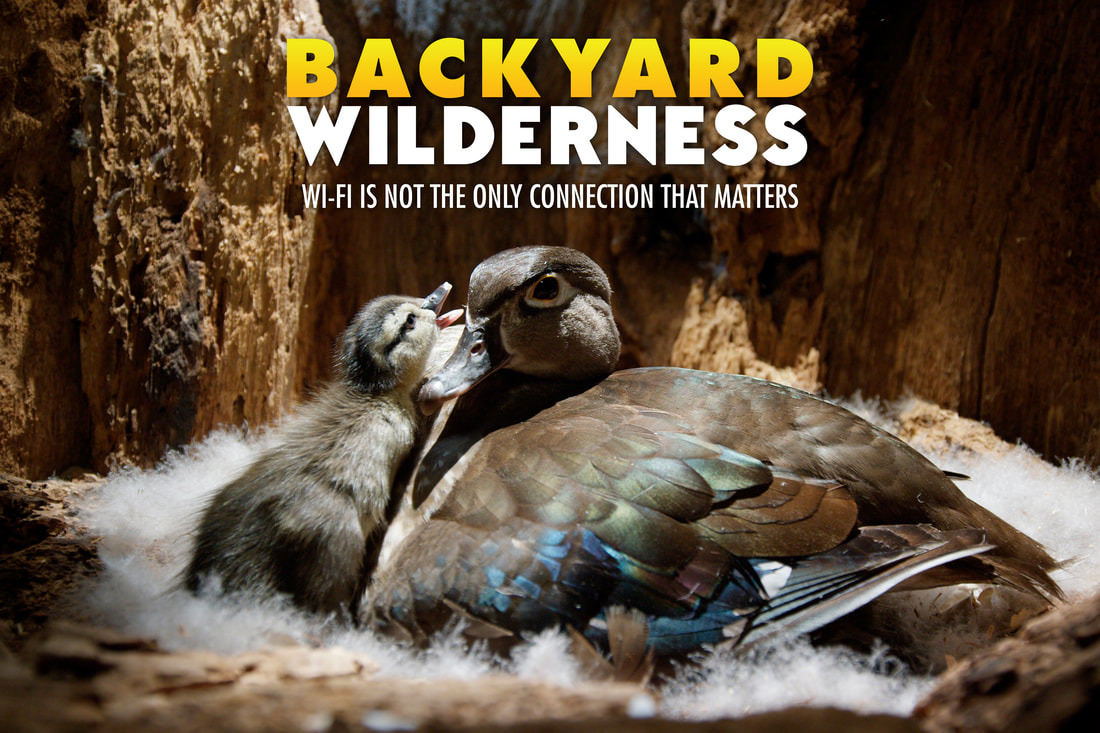

Our movie grew out of our experiences and observations in the woods around our backyard in Westchester County, New York. We have lived in the same place for two decades, and we’ve spent a lot of time outside with our two kids making gardens and exploring the ponds, wetlands, and forest. We also noticed that with the advent of personal electronics, our kids were spending a lot less time in nature than we did growing up. When we read Richard Louv’s book, Last Child in the Woods, we realized that this was a growing phenomenon and we began to think about creating a movie that would inspire kids to get outside and reconnect to nature. The spring migration of the spotted salamander and all the other wildlife “miracles of nature” that we too often overlook became the subject matter that we wove into this story. The story grew rather organically over the course of three years. We wanted to create a narrative about the yearly cycle of animals and plants that live outside a family’s home. Like most families in the digital age, the one in our story live unaware of what’s going on outside – until their 11 year old daughter becomes tuned in to the wonders of nature around them. With input from our science advisors, we worked on filming scenes of the animals that actually live in our backyard, which is part of the Eastern forest ecosystem. For the human characters, we drew on the experiences of our own family. We originally asked our kids to be in the movie, doing typical activities like mowing the lawn, watching TV and waiting at the bus stop, but we eventually had to cast actors because our kids grew up too quickly! The story was kept very simple and told as much as possible from the point of view of the animals and nature. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film? Some of the challenges of the movie were working in snow and freezing temperatures, filming at night, in the rain, 70 feet up in trees, and waist deep in vernal pools. Perhaps the most challenging thing of all was working with the timing of illusive events, like the laying of salamander eggs, the hatching of wood ducklings, and the births of raccoon kits and a fawn. We had to calculate gestation periods precisely, be in the right place at the right time, and be extremely patient. Capturing the growth and seasonal change of plants with time-lapse cameras was also a really challenging process that took many attempts before we got it right. At one point we had three small trees and a host of other plants in our studio along with eight specially programmed cameras operating independently. How do you approach science storytelling? We believe audiences learn science content best when it is an organic part of a story that they have become engaged with, so the key for us is to first put the emphasis on story, and let the science content integrate naturally. We always work directly with scientists to show accurate and illusive behaviors in the natural history scenes. That becomes a driving force in the story. In the case of Backyard Wilderness, we next wrote scenes with our main character engaging in questioning, observing and doing a report on one of the animals whose behavior she studied, much like any field biologist would. Once people are engaged and feel an emotional connection to what they are experiencing, the science content and methods will feel inspiring and will be absorbed by the audience. What impact do you hope this film will have? In the age of personal electronics, kids just aren’t going outside the way we used to. Nature Deficit Disorder is a term coined by Richard Louv to define a growing lack of contact with nature that children and adults are experiencing today. Our lives are now almost 90% indoors and we spend hours in front of computers and on our cell phones. There has been a huge increase in diagnoses of obesity, depression, ADHD, and there is clinical evidence that increased exposure to nature actually reduces these problems and helps people heal. We wanted to create an experience that would inspire the kids of today to reconnect with the wonders of nature occurring all around us and to launch a campaign to get kids to put down their screens and get outside in the natural world. We want to make kids and families feel more actively engaged in their own backyards and parks and hope that our film sparks interest in the sciences and the healthy benefits of outdoor recreational activities like hiking, camping, biking, swimming, geocaching, building forts, and playing in the woods. Were there any surprising or meaningful moments/experiences you want to share? Preparation for one of our centerpiece scenes, the hatching of a nest of wood ducklings and their leap from the nest fifty feet above the ground, really began five years earlier when we first discovered wood ducks nesting in the tree above our house. Later that year, after the ducks had left, a storm blew the tree down. We cut the nest from the fallen tree, rigged it with cameras and bolted it to another tree, close to where the original nest had been. We had no guarantee that the wood ducks would return to the nest, so we were thrilled to see them exploring it just a few days after we put it up. And this time the nest was wired and ready for filming. When the big day arrived, we were ready with numerous remote control cameras rigged around the house and a crew of ten, all gathered around a live feed from the nest with knots in our stomachs. The feeling of amazement and relief after the last duckling made it to the pond was incredible. Working with the human actors who played the kids in the family was also rewarding because they had a chance to experience the woods, butterflies, ducklings and spotted salamanders. We could see that they grew to better appreciate nature during the course of making the film and they loved being a part of something that would inspire other kids. Anything else you would like people to know? For us, Backyard Wilderness is not just a movie. We really want it to be the launching pad for a whole movement aimed at getting nature back into our lives. The film’s goal is to inspire audiences to begin that process. And we’ve partnered with Howard Hughes Medical Institute to get a great educational outreach initiative going alongside the film. We have created one of the most extensive national campaigns ever to help schools and communities reconnect with nature and learn about ecosystem science. The educational outreach campaign includes a Family Activity Guide offering fun outdoor exploration for children and families, a Bioblitz Toolkit that will help schools, libraries and science centers put on local citizen science events, and traveling library/museum/school exhibit displays designed to stimulate interest in outdoor exploration. We have also worked with the California Academy of Sciences’ iNaturalist team to launch a new kid-friendly exploration app called Seek, which will complement the popular iNaturalist app and give kids and families a fun and easy introduction to the world of observation and citizen science. What next? We are working on a number of 3D Giant Screen/IMAX films in the development stage as well as a television series about the relationship between humans and nature. We’re also traveling and giving presentations to expand the educational outreach of Backyard Wilderness as it opens in museum and science center theaters around the world. And specific questions for your Category: What do you feel is most important to remember when telling science stories to younger audiences? You have to make the story entertaining to younger audiences and spark their curiosity. We think it’s important to use science concepts that are at the grade level of the core audience you are targeting. In Backyard Wilderness, we chose to use a young woman narrator, looking back on her life as an 11 year old girl (3-8th grade is our core audience) so kids could relate to someone their own age on the screen. We incorporated contemporary dialogue and activities that young kids experience with their families. To get them excited about the animals outside in their backyards, we juxtaposed some of our own human behaviors with the animals’ behavior to get a chuckle and show kids that animals need many of the same things that we do. Kid are like adults in that they want to be entertained as well as “wowed” by story and visuals.

Answers provided by Executive Producer Dugald Maudsley.

What inspired this story?

DM: Infield Fly Productions has produced five other episodes of Myth or Science for the Nature of Things, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s long-running science and natural history strand. When we were looking to produce our sixth episode we were amazed to discover the extraordinary science being done in the field of feces! Even more interesting was the fact that scientists didn’t see poop as a waste product to be disposed of, they regarded it as something powerful and good that could change our lives. We were hooked. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film? DM: The CBC made it very clear that while they wanted a documentary about poo they didn’t want to see any poo in the documentary – a difficult challenge but one that our director, Jeff Semple, met in a very creative and fun way. The only poo you’ll ever see in this documentary is the stuff left behind by a herd of Holsteins. Otherwise, 44 minutes of documentary about poo without a dookie to be seen. How do you approach science storytelling? DM: We approach science storytelling with two things in mind: provide an insight into cutting edge science in a way that’s accessible and visually exciting. Our goal is to take our audience along with us on a journey of discovery. We don’t want to tell them what we’ve uncovered; we want them to uncover it with us. And we want them to have fun at the same time. Myth or Science is the perfect vehicle for this. It allows our host to become part of the story, to go on a journey with our audience and reveal amazing new science that, we hope, will help change the lives of our viewers. What impact do you hope this film will have? DM: We hope the film has the same impact on other people it had on us; rather than see poo as something to be whisked out of sight, we hope it is now seen as an extraordinary product that can provide clean water, clean energy, help save endangered animals and provide an early warning system when things are going wrong inside our bodies. What next? DM: Next is a documentary about food and how little we know about it and, hopefully, a documentary about longevity. What do you feel is most important to remember when telling science stories to younger audiences? Dr. Jennifer Gardy, Host of Myth or Science: The Power of Poo: “I’d say that for me, engaging young viewers is all about tapping into that “big kid” part of your personality. Kids are naturally curious and enthusiastic about the world around them, and letting that show in your own storytelling - being excited about discovering something or doing an experiment on-screen - really helps take them along on an amazing journey with you!” Why did you pick Dr. Jennifer Gardy to be the on-camera host telling this story? DM: Dr. Jennifer Gardy is an amazing host. She is a microbiologist, but she’s also funny, witty and game to try anything. This is exactly what we need for Myth or Science. Our goal is not to tell our audience what we’ve uncovered but have them come on a journey with us and discover it for themselves. We also want Jennifer to be a guinea pig – experience science personally and illustrate key concepts by experimenting on herself. This makes the science more accessible and interesting. Of course, Jennifer also has the scientific chops. She teaches at the University of British Columbia, she works for the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control and she does basic research. Finally, Jennifer is an awesome communicator. She knows how to explain difficult concepts in an understandable way, how to cut through the confusion that often surrounds scientific subjects and, of course, she has the cred when it comes to speaking to other scientists. AlphaGo Trailer from Jackson Hole WILD on Vimeo.

Answers provided by Director Greg Kohs.

What inspired this story?

GK: Experts predicted that a Go program that could compete with a top professional was at least a decade away. If DeepMind's AlphaGo was able to beat a player of Lee Sedol's stature, it would be a historical achievement with drama and intrigue. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film? GK: Early in my career I worked at NFL Films. That experience, of being able to see the drama on the field while having access to the people and stories unfolding off the field, has always been a fascinating intersection for me. In my recent film, The Great Alone, I was able to explore the epic scale of the Iditarod through the comeback story of a single competitor. In AlphaGo, the competition between man and machine provided a similar backdrop, albeit with far larger consequences. How do you approach science storytelling? GK: The complexity of the game of Go, combined with the technical depth of an emerging technology like artificial intelligence seemed like it might create an insurmountable barrier for a film like this. The fact that I was so innocently unaware of Go and AlphaGo actually proved to be beneficial. It allowed me to approach the action and interviews with pure curiosity, the kind that helps make any subject matter emotionally accessible.

Answers provided by Writer and Director Annamaria Talas.

What inspired this story?

AT: Like most people, I didn't pay much attention to fungi, let alone thinking of making a film about them. But once I saw Australian photographer's, Steve Axford's amazing mushroom time-lapse images I became spellbound by their enigmatic beauty. Their diversity, vibrant colours, bizarre shapes made me curious. What was going on here? And as I started to dig into Google Scholar I became 'curiouser and curiouser'. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film? AT: When I began investigating this strange realm, it soon became apparent that there was a lot to reveal, as there was a huge gap in knowledge. Little did I realize that I'd chosen such a fast-evolving field of research that I would need to rewrite the script several times before the shoot. Fungi are weird, largely overlooked, and still little studied, without institutes dedicated to fungal research and few scientists willing to devote their careers to revealing their many secrets. But slowly the story is being revealed. How do you approach science storytelling? AT: As with my previous films, it became a matter of bringing together different lines of research into a compelling narrative. I firmly believe that context and story-telling are essential to understanding. By unfolding the story over a billion years of evolution, I focused on the fundamental role fungi have played in life on land. What impact do you hope this film will have? AT: A one hour documentary is barely enough to go beyond the highlights but our hope is that this film puts fungi on our horizon and from now on, every time viewers look at a button mushroom in a grocery store they’ll see them in a very different way: they are the unlikely conductors of the symphony of life on land. I also hope, the evolutionary and ecological context illuminates just how carefully life on Earth is balanced and makes the audience aware of the dangers of human induced changes. It's more important than ever to understand fungi. Were there any surprising or meaningful moments/experiences you want to share? AT: The incredible realization that without fungi, we wouldn't be here. The notion that in our increasingly warming world our mostly beneficial relationship with these organisms could change, turning them from friends into foes. The idea that fungi represent a third mode of life: organisms that are networks. Anything else you would like people to know? AT: As we say in the film, fungi represent both a dire threat and a tremendous opportunity to humanity. So, it’s well and truly time to get to know them. What next? AT: My next documentary is a deep dive into computational sociology that reveals how does success emerge. Why is it that no matter how hard you work, perfect your performance, accomplish amazing things, you can still fail? We’ll show that performance and success are governed by different mathematical laws and we’ll reveal the invisible forces that drive our chances of success day after day. Our aim is to demystify success and offer guidance, rooted in science to navigate our individual journeys to success. Did the film team use any unusual techniques or unique imaging technology? AT: The visual highlight of the film is Stephen Axford’s unique time-lapses that are produced in two sheds on his property in tropical Queensland, he jokingly calls his fungariums. In these sheds, Axford creates the perfect conditions for wild forest fungus to grow on wood brought in from outside. The time-lapses can take anything from a few days to a month, and so require a controlled environment to produce. There are three individual time-lapse studio set ups in the sheds, where the fungus is placed in front of cameras, tracks and lighting, with backgrounds to mimic the forest. A diverse range of cameras are used from Sony A7r II to various older canon cameras – which all have to be robust to survive the warm and consistently damp conditions that mushrooms love and need. Because the photographs can be taken at slow shutter speeds the lighting is very minimal – cheap LEDs – mounted to replicate the lighting in the forest. The fungarium sheds have enabled Stephen Axford to record time-lapses on currently over 30 species of fungi and at the same time observe how they grows over many seasons. Our next challenge was to match the beauty of these specialist images with the rest of our filming. For this it was vital to get on-the-ground in unique environments from lava-fields of Iceland to the deep forests of British Columbia. This is highly reliant on the seasons, so filming took place over a very extended period. We used the latest cameras from Blackmagic and Panasonic to ensure a rich colour depth. Finally, we discovered some remarkable images from artists Tarek Mawad and Friedrich van Schoor. They spent months projection mapping video images in a forest, bringing magic onto plants, animals and fungi. Their project, called ‘The Bioluminescent Forest’ had just the aesthetic I was looking for: the beautiful mysteries of nature that remain hidden from us. Just like fungi themselves.

Answers provided by Producer and Director Neil Losin.

What inspired this story?

NL: Directors Neil Losin and Nate Dappen both earned their PhDs studying lizards, so they knew that lizards called “anoles” have played, and continue to play, a pivotal role in our collective understanding of evolution and ecology. Yet to our knowledge, no one had ever made a documentary about them. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film? NL: The challenge was making a story about very small lizards feel like a very big deal. We hope that our own excitement about the story and the enthusiasm of the featured scientists about their small-but-charismatic research subjects accomplishes that. How do you approach science storytelling? NL: We like to collaborate with scientists from the inception of a project, all the way through to the final delivery. In this case, our primary collaborator was the Godfather of anole research, Jonathan Losos. We worked together to get funding for the film, chose the scientists to feature, shaped the story, and – when we were in the field – tracked down a whole bunch of really cool lizards. What impact do you hope this film will have? NL: Anoles are lizards that many people can find in their own backyards. We hope that this film encourages people to take a closer look at the nature all around them… you never know when that lizard or insect perched on your garden hose is actually a creature that transformed our scientific understanding of life. Were there any surprising or meaningful moments/experiences you want to share? NL: With the help of an anole researcher named Luke Mahler and his all-star field crew, we were able to find a very rare anole in the Dominican Republic – a species that had only been described to science in 2016. We were the first camera crew to film it. Both of us (Nate and Neil) were unexpectedly moved by the experience of finding and filming this creature. What a privilege to capture and preserve a sight that few others have ever witnessed! (Of course, it’s easy to get emotional when you’re delirious from lack of sleep after spending two long nights searching in the dark for an exceedingly well camouflaged sleeping lizard.) What next? NL: I think the world won’t be ready for another anole film for at least a couple years… So we’re moving on to other stories. We’ve got plenty of projects in the pipeline, but one we’re excited about involves the evolution of color vision, and focuses on some of the coolest invertebrates around: jumping spiders! Digits Trailer from Jackson Hole WILD on Vimeo.

Answers provided by Executive Producer Noah Morowitz.

What inspired this story?

NM: CuriosityStream founder John Hendricks came up with the concept of producing multiple hours on the past, present and future of the internet. He was struck by the fact that even though technology increasingly dominates our lives, very few people have a basic understanding of how we got here. From the seemingly simple – how does an email get from point A to point B? – to complex issues of man/machine interface, there is no end to the profound influence of DIGITS. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. NM: The story of Internet security is difficult to tell: much of the material is highly technical and both the good guys and the bad guys are reluctant to reveal too much! We were able to get insider access through our existing relationship with the U.S. Secret Service and by taking the time to gain the trust of key players. How do you approach science storytelling? NM: The general public is fascinated by science if it is presented not as facts and figures but as stories and characters. We focused on the people and events that drove the development of the internet, the key turning points in this modern revolution. What impact do you hope this film will have? NM: Internet giants are reluctant to acknowledge that the monetization of personal data is how they make money. We hope the film helps people to understand the myriad ways web technology and practices modify human behavior – for better and for worse. Were there any surprising or meaningful moments/experiences you want to share? NM: We were fortunate to have the opportunity to interview NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden in Moscow. He brought the issue of personal privacy into sharp focus with his statement: “Saying you don’t care about surveillance because you have nothing to hide is like saying that you don’t care about freedom of speech because you have nothing to say. These are fundamental rights.” Anything else you would like people to know? NM: Some people believe that the internet is the most important human invention since the printing press; others compare the web to the invention of the alphabet. Either way, if you want to understand your world you need to take a long look at this mysterious new force that surrounds us. What next? NM: We hope to make additional hours of DIGITS, covering such topics as The Internet of Things, Future Money and How We’ll Think and How We’ll Love. Deep Look Trailer from Jackson Hole WILD on Vimeo.

Answers provided by Producer Gabriela Quirós.

Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film.

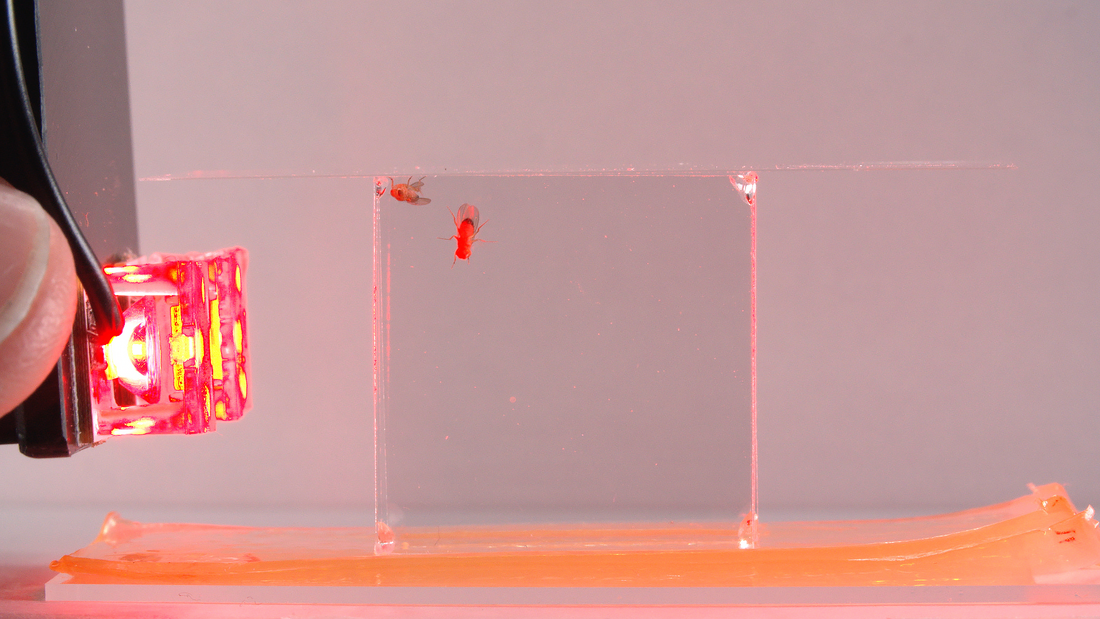

GQ: The biggest challenge in filming this episode was containing the fruit flies in a square, glass receptacle that was small enough. In this case, the scientist whose fruit flies we were filming, Eric Hoopfer, from Caltech, in Pasadena, is very good at building tiny glass boxes because he himself has filmed his flies as part of his research. So Eric built us a few boxes by gluing together very thin glass slips that are used to put samples under the microscope. These boxes were tiny – narrower than your finger. How do you approach science storytelling? GQ: I try to prepare as much as possible before we go out filming to try and understand what we can expect to see. And then I hope that in addition to the behaviors we’re planning to film, we’ll also end up being surprised with something we didn’t expect to see. What impact do you hope this film will have? GQ: I hope that it makes folks appreciate how exciting and weird scientific research can be. We don’t get to do too many stories about genetic engineering, because it’s difficult to show the effects of the engineering. So this story was a unique opportunity to talk about genetic engineering in a compelling way. Were there any surprising or meaningful moments/experiences you want to share? GQ: Watching those fighting fruit flies is very entertaining, and Josh’s camera work made it possible to observe their behaviors in quite some detail, so much so that Caltech neuroscientist David J. Anderson, whose lab we filmed in, licensed the footage from KQED to use in his research. So our footage of fighting fruit flies could one day show up in a scientific publication! Anything else you would like people to know? GQ: This episode pairs fighting fruit flies with a score inspired by Bruce Lee movies. How great is that? What next? GQ: I’m working on a story about planarians -- flatworms with two tiny eyes that make them look like cartoon characters. They’re similar to fruit flies in that they’re used for many different kinds of scientific research. They’re even cooler than fruit flies because they can regenerate. It’s as if you could grow a new you out of a part of you.

Answers provided by Gary Weimberg, Co-Director and Co-Producer

What inspired this story?

GW: Evidence based good news. We wanted to make a film that was different, not another film about dangers in the environment, or emerging pathological problems, or even injustices that needed to be corrected. We had done films on all of those and wanted to cheer ourselves up … and the audience. But not with false hopes, nor with ostrich head-in-the-sand essays. We wanted … Evidence based good news. The science of Dr. Marian Diamond is exactly that. Her work was always about the capacity of the brain, the capabilities of the brain, the miraculous form and function of the brain … within a solid scientific context. The prime example, her research establishing brain plasticity. It was her work that, for the first time, measured precise anatomical changes associated with plasticity in rat brains, pioneering research that decisively transformed neural plasticity from a controversial speculative idea to a measurable, indisputable, observable function and core ability of the brain. Her battle for the acceptance of plasticity was hard fought but by now, nearly universally accepted. Her research marked a profound paradigm shift in science, in our understanding of the brain and thus … in our understanding of ourselves. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film? GW: We thought this would be an easy charming film, far from the controversial topics we had previously made films about. We thought … what could be controversial about science … and then the war on science began, led by the climate change deniers. We thought … what could be controversial about a charming gracious elderly woman … and then the war on women broke out with renewed fanaticism and fervor. How do you approach science storytelling? We wanted to tell a HUMAN science story. The fallacy implicit in coverage of state-of-the-art, bleeding edge, breakthrough science is that it that science is presented as one break thru after another, an endless forward march. But in fact, the general public often just becomes confused as the waves of advances first suggest that coffee is good for you, then that it is bad for you, then that it is good for you again. Overall, science storytelling is FAILING to convince the general public that science can and should be trusted. The power of the climate change deniers is brutally vivid illustration of this failure. Our choice was to approach science storytelling as a HUMAN story. Our approach was biographical, knowing that this allows the audience a ready and easy entry point. What impact do you hope this film will have? Firstly, Dr. Diamond was a neglected, under-reported scientific hero when we began this film. After the broadcast, and after her passing away within a few months after the films premiere, in obituary after obituary around the world, she was recognized as “one of the founders of modern neuroscience.” In large part, this is directly because of the attention the film inspired for the wonderful life’s work of this wonderful scientist. We trust that this film, and the honor of awards like these, will allow her legacy to be as it should be, a known and appreciated bright light in the history of great scientists, especially great women scientists. Secondly, we wanted to raise up a profoundly engaging and inspirational story of a role model in science. Someone whose life and work would make ANY viewer think, “I could spend my life doing that…” but especially, a film that would inspire women and girls in STEM. We already have had screenings for incredibly diverse female audiences, including Girl Scout troup 420 who not only watched the film, but created a “Marian Diamond Neuroscience Merit Badge.” Dr Diamond demonstrated by her very life that one answer to gender based oppression is a life well lived, that the gender inequalities Dr. Diamond faced can be effectively challenged and even disassembled simply by pointing out what she did … and allow the world changing work to speak for itself. Were there any surprising or meaningful moments/experiences you want to share? From shoot day 1 to Emmy nomination notice day was 8 years. Over that time Dr. Diamond and her husband Dr. Arnie Schiebel transformed first into documentary subjects, then into our good friend, and before the end they became our best friends, whose company we sought out and deeply enjoyed on every level. We were their final students, returning again and again to their home with questions and confustion, to review the film and the scientific concpets for accuracy and effective communications. They became true members of our team, our scientific co-filmmakers. And thru all that … we laughed. Such conversations we had! What an honor to engage so deeply with two wise elders who had traveled the world seeking ever more knowledge about the brain, both to learn and to dissiminate. As we filmed, they retired from teaching and moved into the senior housing. We completed the film in a race against mortality, knowing that both of them were increasingly frail. It was our most profound wish to NOT need to film at a funeral, to NOT need to close the film with an obituary. We accomplished that, in a timely enough manner that although they are not alive today to enjoy this honor, they did enjoy a full year of film festivals and awards and the joy of the broadcast on PBS stations across the US. So very pleased to have accomplished that for our dear, dear friends. Why did you pick to be the on-camera host telling this story? If ever there was an appropriate ambassador for science, it is Dr. Marian Diamond. A beloved professor whose classes on human anatomy at UC Berkeley were legendarily popular, the most popular on campus, she also was described by the NYTIMES in 2010 as the second most popular college professor in the world, based on the millions of views of her YouTube anatomy lecture series.

Answers provided by Terri Randall, Writer/Producer/Director of "Death Dive to Saturn"

What inspired this story?

Terri Randall: Cassini’s final moments inspired the story. The Cassini Mission to Saturn, one of the most successful missions in NASA’s history, was coming to an end. NOVA made a commitment to document the extraordinary discoveries the team made, as well as capture the spacecraft’s fiery end. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film? TR: Telling a story about space exploration is always exciting but also challenging—you can’t shoot on location! Although the Cassini Mission produced thousands of stunning images we wanted to develop ways to make the solar system more tangible. In one scene we combined live action with animation to bring a lake on Saturn’s moon Titan to life. It was also a challenge to tell the story of such a long and successful mission: what discoveries to include, which stories will resonate with the audience? Instead of trying to tell the story chronologically we broke it into three acts-- the story of the planet, the story of Saturn’s moons and the story of Saturn’s rings. A logistical challenge was documenting the mission’s end. It happened in the middle of the night and the team (about a thousand team members were there) was split between two locations. Figuring out the best way to cover it was a challenging experience. How do you approach science storytelling? TR: I don’t come from a science background and while it takes me time to research and understand a subject, once I do, I think I have an intuitive sense of how to share what I’ve learned with the audience. It’s too easy to get lost in scientific information so I try to keep the science as simple and accessible as possible and always keep in mind that I’m telling a story with a beginning, middle and an end, to always keep the arc of the story in mind and not get lost in the details. What impact do you hope this film will have? TR: I hope the film will be used for years to come to convey the enormous accomplishments of this mission-- an evergreen of the mission’s discoveries. Were there any surprising or meaningful moments/experiences you want to share? TR: The way the scientists talked about the spacecraft was truly endearing. After 20 years it had become a good friend. Having the opportunity to witness its demise with the team was an extraordinary experience. There were many tears. Anything else you would like people to know? TR: I really enjoyed working with the team, scientists who explore space, trying to answer some of our biggest scientific mysteries, are inspiring. What next? TR: I’m working on an hour for NOVA on another NASA mission, New Horizons, the mission that brought us our first up close images of Pluto. On New Year’s Day the spacecraft will fly by an object in the far reaches of the solar system, it will be the furthest fly by in the history of space exploration. |

AuthorAs the curators of the Science Media Awards Summit in the Hub (SMASH), we believe storytelling is a common thread in our shared human experience, and that new media allows us to convey the wonders of scientific discovery in new and compelling ways. Archives

October 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed