|

Answers provided by Director Nicholas Brown.

What inspired this story?

NB: This story was inspired by the book “The Serengeti Rules” by Sean Carroll, who had started his research after making a trip to the Serengeti and his kids asked him “how come this place has so much more wildlife than anywhere else?” He didn’t learn the answer until he started talking to the people this film is about. Describe some of the challenges while making this film. NB: The science behind the film is intensive, controversial and in many respects brand new, so we had to learn a lot about ecology in a short period of time. (In development we had three PhD’s on our research team). This is also a story with a lot of characters and storylines that cover the entire globe. The hardest part was deciding what not to film! We also were unconvinced there was a way to knit together all of these diverging threads in different ecosystems. In the end we narrowed it down to just 5 scientists and locations, and that is the story that emerges. How do you approach science storytelling? NB: We feel it is essential that audiences be given an emotional connection to the story, especially when the subject matter is as intellectual as this is. In this case we used dramatic reconstruction to draw people closer to the key characters. We hope that you, the viewer will fall in love with nature just as our characters did. We also feel the science is easier to comprehend if you have a fully rounded human being that you can identify with and follow through the story. We let our characters tell their personal journeys without resorting to narration. This unfiltered approach is a way of showing the audience respect, and trusting that they will figure out the difficult bits on their own. What impact do you hope this film will have? NB: In some ways the film is already having the impact we hoped for most, and that is inspiring younger people—especially those aged 10- 21—to fall in love with ecology. Biodiversity loss and extinction are depressing issues, so it is important that we project a story that also has some hope. We notice that young audiences are really latching onto this positive message. Ultimately, we hope that the science and the people will inspire everyone who watches the film. The best quotes-- and we’ve heard this more than once--come from 11 year olds saying, “When I grow up I want to be an ecologist!” Were there any surprising or meaningful moments/experiences you want to share? NB: Early in the process we knew we had to film the man who got this story going: Bob Paine. We’d set a date to make him the first person we would interview. But not long after agreeing a date, Bob called us to say that he was ill, but was still eager to take part in the film. Then, just a week before the interview, Bob’s daughter called to say he might not live to see the morning. We were shocked, and more than a little depressed. We cancelled our plans to film Bob, and were considering cancelling the whole film when Bob emailed. He said that he wanted to film with us no matter what. He wanted to get this story out there. On the day we arrived, Bob had just a matter of minutes per day where he was even awake and able to speak. He gave us 20 minutes per day on two consecutive days to interview him. Can you imagine, being on your deathbed, in agonizing pain, willing to talk to a film crew? You see, for Bob his work was so much more than a job. It was his passion and his mission, and he wanted to share what he had learned right up to his dying breath. He passed away less than a week after we finished the interview. The film is dedicated to his memory.

What next?

NB: The next step for us is to get this film distributed as widely as possible. We have plans to get it into schools and classrooms. And we hope to find distribution to the widest possible audience. Editing: What are the specific editing challenges you had to address? NB: We decided early on that we wanted the audience to have a direct cinematic experience, unfiltered by a narrator. This meant working with days if not weeks worth of interviews, and threading together a story that we hope people can follow with ease. Science, especially when it is new, is not always easy to explain or understand. Often there isn’t even a language for what you are trying to get across. We literally had to coin the term “upgrading” (instead of phrases like “trophic cascade restoration) to make the film understandable. Interestingly, the term “upgrading” is starting to crop amongst scientists now. Where there any unexpected surprises or breakthroughs during this film investigation? “The Serengeti Rules” is based on the book by Sean Carroll. At first glance, it was hard to see how this book—which journeys from molecular biology to medicine and finally to ecology—would make a film. Feature documentaries work best when they follow a single narrative thread—and better yet, a single character. Once we narrowed this story down to 5 scientists, we had the first glimpse that we might be able to tell this story with a film. What kept us going was the importance of the subject matter. The breakthroughs happened over the course of 50 years and 5 lifetimes of intensive study. Ultimately, the discovery these scientists made is profound, and it will change how conservation is done from now on.

1 Comment

Answers provided by Producer/Directors (or Filmmakers) Andrew Young and Susan Todd.

What inspired this story?

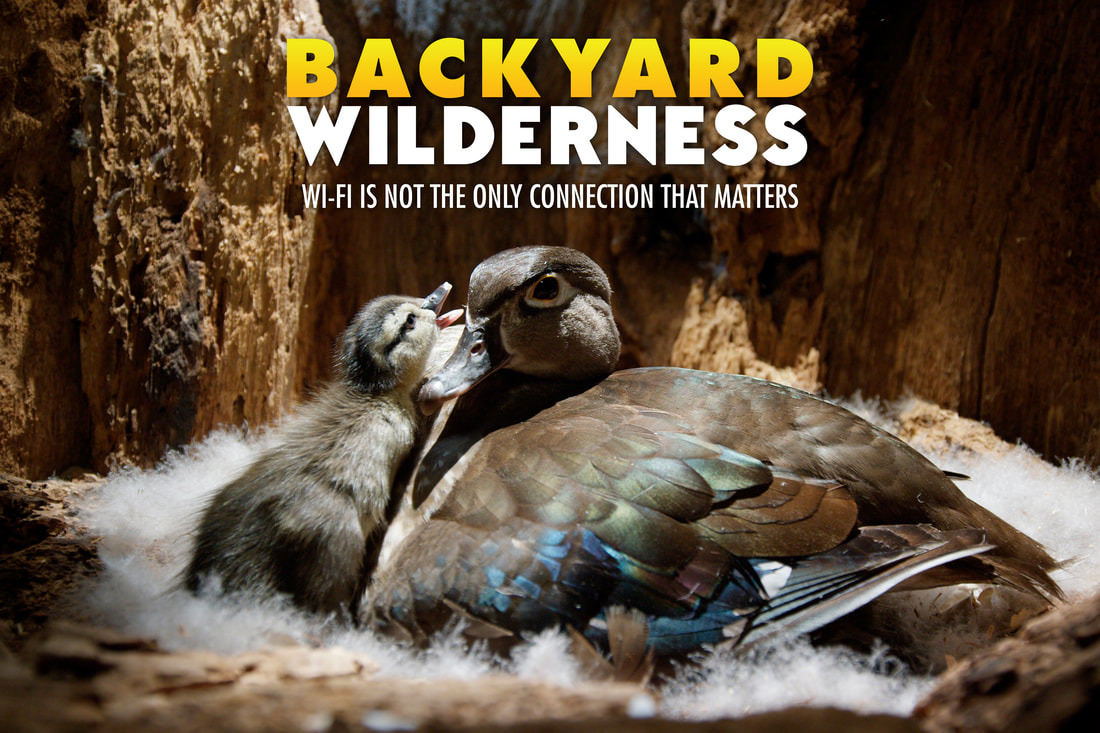

Our movie grew out of our experiences and observations in the woods around our backyard in Westchester County, New York. We have lived in the same place for two decades, and we’ve spent a lot of time outside with our two kids making gardens and exploring the ponds, wetlands, and forest. We also noticed that with the advent of personal electronics, our kids were spending a lot less time in nature than we did growing up. When we read Richard Louv’s book, Last Child in the Woods, we realized that this was a growing phenomenon and we began to think about creating a movie that would inspire kids to get outside and reconnect to nature. The spring migration of the spotted salamander and all the other wildlife “miracles of nature” that we too often overlook became the subject matter that we wove into this story. The story grew rather organically over the course of three years. We wanted to create a narrative about the yearly cycle of animals and plants that live outside a family’s home. Like most families in the digital age, the one in our story live unaware of what’s going on outside – until their 11 year old daughter becomes tuned in to the wonders of nature around them. With input from our science advisors, we worked on filming scenes of the animals that actually live in our backyard, which is part of the Eastern forest ecosystem. For the human characters, we drew on the experiences of our own family. We originally asked our kids to be in the movie, doing typical activities like mowing the lawn, watching TV and waiting at the bus stop, but we eventually had to cast actors because our kids grew up too quickly! The story was kept very simple and told as much as possible from the point of view of the animals and nature. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film? Some of the challenges of the movie were working in snow and freezing temperatures, filming at night, in the rain, 70 feet up in trees, and waist deep in vernal pools. Perhaps the most challenging thing of all was working with the timing of illusive events, like the laying of salamander eggs, the hatching of wood ducklings, and the births of raccoon kits and a fawn. We had to calculate gestation periods precisely, be in the right place at the right time, and be extremely patient. Capturing the growth and seasonal change of plants with time-lapse cameras was also a really challenging process that took many attempts before we got it right. At one point we had three small trees and a host of other plants in our studio along with eight specially programmed cameras operating independently. How do you approach science storytelling? We believe audiences learn science content best when it is an organic part of a story that they have become engaged with, so the key for us is to first put the emphasis on story, and let the science content integrate naturally. We always work directly with scientists to show accurate and illusive behaviors in the natural history scenes. That becomes a driving force in the story. In the case of Backyard Wilderness, we next wrote scenes with our main character engaging in questioning, observing and doing a report on one of the animals whose behavior she studied, much like any field biologist would. Once people are engaged and feel an emotional connection to what they are experiencing, the science content and methods will feel inspiring and will be absorbed by the audience. What impact do you hope this film will have? In the age of personal electronics, kids just aren’t going outside the way we used to. Nature Deficit Disorder is a term coined by Richard Louv to define a growing lack of contact with nature that children and adults are experiencing today. Our lives are now almost 90% indoors and we spend hours in front of computers and on our cell phones. There has been a huge increase in diagnoses of obesity, depression, ADHD, and there is clinical evidence that increased exposure to nature actually reduces these problems and helps people heal. We wanted to create an experience that would inspire the kids of today to reconnect with the wonders of nature occurring all around us and to launch a campaign to get kids to put down their screens and get outside in the natural world. We want to make kids and families feel more actively engaged in their own backyards and parks and hope that our film sparks interest in the sciences and the healthy benefits of outdoor recreational activities like hiking, camping, biking, swimming, geocaching, building forts, and playing in the woods. Were there any surprising or meaningful moments/experiences you want to share? Preparation for one of our centerpiece scenes, the hatching of a nest of wood ducklings and their leap from the nest fifty feet above the ground, really began five years earlier when we first discovered wood ducks nesting in the tree above our house. Later that year, after the ducks had left, a storm blew the tree down. We cut the nest from the fallen tree, rigged it with cameras and bolted it to another tree, close to where the original nest had been. We had no guarantee that the wood ducks would return to the nest, so we were thrilled to see them exploring it just a few days after we put it up. And this time the nest was wired and ready for filming. When the big day arrived, we were ready with numerous remote control cameras rigged around the house and a crew of ten, all gathered around a live feed from the nest with knots in our stomachs. The feeling of amazement and relief after the last duckling made it to the pond was incredible. Working with the human actors who played the kids in the family was also rewarding because they had a chance to experience the woods, butterflies, ducklings and spotted salamanders. We could see that they grew to better appreciate nature during the course of making the film and they loved being a part of something that would inspire other kids. Anything else you would like people to know? For us, Backyard Wilderness is not just a movie. We really want it to be the launching pad for a whole movement aimed at getting nature back into our lives. The film’s goal is to inspire audiences to begin that process. And we’ve partnered with Howard Hughes Medical Institute to get a great educational outreach initiative going alongside the film. We have created one of the most extensive national campaigns ever to help schools and communities reconnect with nature and learn about ecosystem science. The educational outreach campaign includes a Family Activity Guide offering fun outdoor exploration for children and families, a Bioblitz Toolkit that will help schools, libraries and science centers put on local citizen science events, and traveling library/museum/school exhibit displays designed to stimulate interest in outdoor exploration. We have also worked with the California Academy of Sciences’ iNaturalist team to launch a new kid-friendly exploration app called Seek, which will complement the popular iNaturalist app and give kids and families a fun and easy introduction to the world of observation and citizen science. What next? We are working on a number of 3D Giant Screen/IMAX films in the development stage as well as a television series about the relationship between humans and nature. We’re also traveling and giving presentations to expand the educational outreach of Backyard Wilderness as it opens in museum and science center theaters around the world. And specific questions for your Category: What do you feel is most important to remember when telling science stories to younger audiences? You have to make the story entertaining to younger audiences and spark their curiosity. We think it’s important to use science concepts that are at the grade level of the core audience you are targeting. In Backyard Wilderness, we chose to use a young woman narrator, looking back on her life as an 11 year old girl (3-8th grade is our core audience) so kids could relate to someone their own age on the screen. We incorporated contemporary dialogue and activities that young kids experience with their families. To get them excited about the animals outside in their backyards, we juxtaposed some of our own human behaviors with the animals’ behavior to get a chuckle and show kids that animals need many of the same things that we do. Kid are like adults in that they want to be entertained as well as “wowed” by story and visuals.

Answers provided by Executive Producer Dugald Maudsley.

What inspired this story?

DM: Infield Fly Productions has produced five other episodes of Myth or Science for the Nature of Things, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s long-running science and natural history strand. When we were looking to produce our sixth episode we were amazed to discover the extraordinary science being done in the field of feces! Even more interesting was the fact that scientists didn’t see poop as a waste product to be disposed of, they regarded it as something powerful and good that could change our lives. We were hooked. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film? DM: The CBC made it very clear that while they wanted a documentary about poo they didn’t want to see any poo in the documentary – a difficult challenge but one that our director, Jeff Semple, met in a very creative and fun way. The only poo you’ll ever see in this documentary is the stuff left behind by a herd of Holsteins. Otherwise, 44 minutes of documentary about poo without a dookie to be seen. How do you approach science storytelling? DM: We approach science storytelling with two things in mind: provide an insight into cutting edge science in a way that’s accessible and visually exciting. Our goal is to take our audience along with us on a journey of discovery. We don’t want to tell them what we’ve uncovered; we want them to uncover it with us. And we want them to have fun at the same time. Myth or Science is the perfect vehicle for this. It allows our host to become part of the story, to go on a journey with our audience and reveal amazing new science that, we hope, will help change the lives of our viewers. What impact do you hope this film will have? DM: We hope the film has the same impact on other people it had on us; rather than see poo as something to be whisked out of sight, we hope it is now seen as an extraordinary product that can provide clean water, clean energy, help save endangered animals and provide an early warning system when things are going wrong inside our bodies. What next? DM: Next is a documentary about food and how little we know about it and, hopefully, a documentary about longevity. What do you feel is most important to remember when telling science stories to younger audiences? Dr. Jennifer Gardy, Host of Myth or Science: The Power of Poo: “I’d say that for me, engaging young viewers is all about tapping into that “big kid” part of your personality. Kids are naturally curious and enthusiastic about the world around them, and letting that show in your own storytelling - being excited about discovering something or doing an experiment on-screen - really helps take them along on an amazing journey with you!” Why did you pick Dr. Jennifer Gardy to be the on-camera host telling this story? DM: Dr. Jennifer Gardy is an amazing host. She is a microbiologist, but she’s also funny, witty and game to try anything. This is exactly what we need for Myth or Science. Our goal is not to tell our audience what we’ve uncovered but have them come on a journey with us and discover it for themselves. We also want Jennifer to be a guinea pig – experience science personally and illustrate key concepts by experimenting on herself. This makes the science more accessible and interesting. Of course, Jennifer also has the scientific chops. She teaches at the University of British Columbia, she works for the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control and she does basic research. Finally, Jennifer is an awesome communicator. She knows how to explain difficult concepts in an understandable way, how to cut through the confusion that often surrounds scientific subjects and, of course, she has the cred when it comes to speaking to other scientists. AlphaGo Trailer from Jackson Hole WILD on Vimeo.

Answers provided by Director Greg Kohs.

What inspired this story?

GK: Experts predicted that a Go program that could compete with a top professional was at least a decade away. If DeepMind's AlphaGo was able to beat a player of Lee Sedol's stature, it would be a historical achievement with drama and intrigue. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film? GK: Early in my career I worked at NFL Films. That experience, of being able to see the drama on the field while having access to the people and stories unfolding off the field, has always been a fascinating intersection for me. In my recent film, The Great Alone, I was able to explore the epic scale of the Iditarod through the comeback story of a single competitor. In AlphaGo, the competition between man and machine provided a similar backdrop, albeit with far larger consequences. How do you approach science storytelling? GK: The complexity of the game of Go, combined with the technical depth of an emerging technology like artificial intelligence seemed like it might create an insurmountable barrier for a film like this. The fact that I was so innocently unaware of Go and AlphaGo actually proved to be beneficial. It allowed me to approach the action and interviews with pure curiosity, the kind that helps make any subject matter emotionally accessible.

Answers provided by Writer and Director Annamaria Talas.

What inspired this story?

AT: Like most people, I didn't pay much attention to fungi, let alone thinking of making a film about them. But once I saw Australian photographer's, Steve Axford's amazing mushroom time-lapse images I became spellbound by their enigmatic beauty. Their diversity, vibrant colours, bizarre shapes made me curious. What was going on here? And as I started to dig into Google Scholar I became 'curiouser and curiouser'. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film? AT: When I began investigating this strange realm, it soon became apparent that there was a lot to reveal, as there was a huge gap in knowledge. Little did I realize that I'd chosen such a fast-evolving field of research that I would need to rewrite the script several times before the shoot. Fungi are weird, largely overlooked, and still little studied, without institutes dedicated to fungal research and few scientists willing to devote their careers to revealing their many secrets. But slowly the story is being revealed. How do you approach science storytelling? AT: As with my previous films, it became a matter of bringing together different lines of research into a compelling narrative. I firmly believe that context and story-telling are essential to understanding. By unfolding the story over a billion years of evolution, I focused on the fundamental role fungi have played in life on land. What impact do you hope this film will have? AT: A one hour documentary is barely enough to go beyond the highlights but our hope is that this film puts fungi on our horizon and from now on, every time viewers look at a button mushroom in a grocery store they’ll see them in a very different way: they are the unlikely conductors of the symphony of life on land. I also hope, the evolutionary and ecological context illuminates just how carefully life on Earth is balanced and makes the audience aware of the dangers of human induced changes. It's more important than ever to understand fungi. Were there any surprising or meaningful moments/experiences you want to share? AT: The incredible realization that without fungi, we wouldn't be here. The notion that in our increasingly warming world our mostly beneficial relationship with these organisms could change, turning them from friends into foes. The idea that fungi represent a third mode of life: organisms that are networks. Anything else you would like people to know? AT: As we say in the film, fungi represent both a dire threat and a tremendous opportunity to humanity. So, it’s well and truly time to get to know them. What next? AT: My next documentary is a deep dive into computational sociology that reveals how does success emerge. Why is it that no matter how hard you work, perfect your performance, accomplish amazing things, you can still fail? We’ll show that performance and success are governed by different mathematical laws and we’ll reveal the invisible forces that drive our chances of success day after day. Our aim is to demystify success and offer guidance, rooted in science to navigate our individual journeys to success. Did the film team use any unusual techniques or unique imaging technology? AT: The visual highlight of the film is Stephen Axford’s unique time-lapses that are produced in two sheds on his property in tropical Queensland, he jokingly calls his fungariums. In these sheds, Axford creates the perfect conditions for wild forest fungus to grow on wood brought in from outside. The time-lapses can take anything from a few days to a month, and so require a controlled environment to produce. There are three individual time-lapse studio set ups in the sheds, where the fungus is placed in front of cameras, tracks and lighting, with backgrounds to mimic the forest. A diverse range of cameras are used from Sony A7r II to various older canon cameras – which all have to be robust to survive the warm and consistently damp conditions that mushrooms love and need. Because the photographs can be taken at slow shutter speeds the lighting is very minimal – cheap LEDs – mounted to replicate the lighting in the forest. The fungarium sheds have enabled Stephen Axford to record time-lapses on currently over 30 species of fungi and at the same time observe how they grows over many seasons. Our next challenge was to match the beauty of these specialist images with the rest of our filming. For this it was vital to get on-the-ground in unique environments from lava-fields of Iceland to the deep forests of British Columbia. This is highly reliant on the seasons, so filming took place over a very extended period. We used the latest cameras from Blackmagic and Panasonic to ensure a rich colour depth. Finally, we discovered some remarkable images from artists Tarek Mawad and Friedrich van Schoor. They spent months projection mapping video images in a forest, bringing magic onto plants, animals and fungi. Their project, called ‘The Bioluminescent Forest’ had just the aesthetic I was looking for: the beautiful mysteries of nature that remain hidden from us. Just like fungi themselves. |

AuthorAs the curators of the Science Media Awards Summit in the Hub (SMASH), we believe storytelling is a common thread in our shared human experience, and that new media allows us to convey the wonders of scientific discovery in new and compelling ways. Archives

October 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed