|

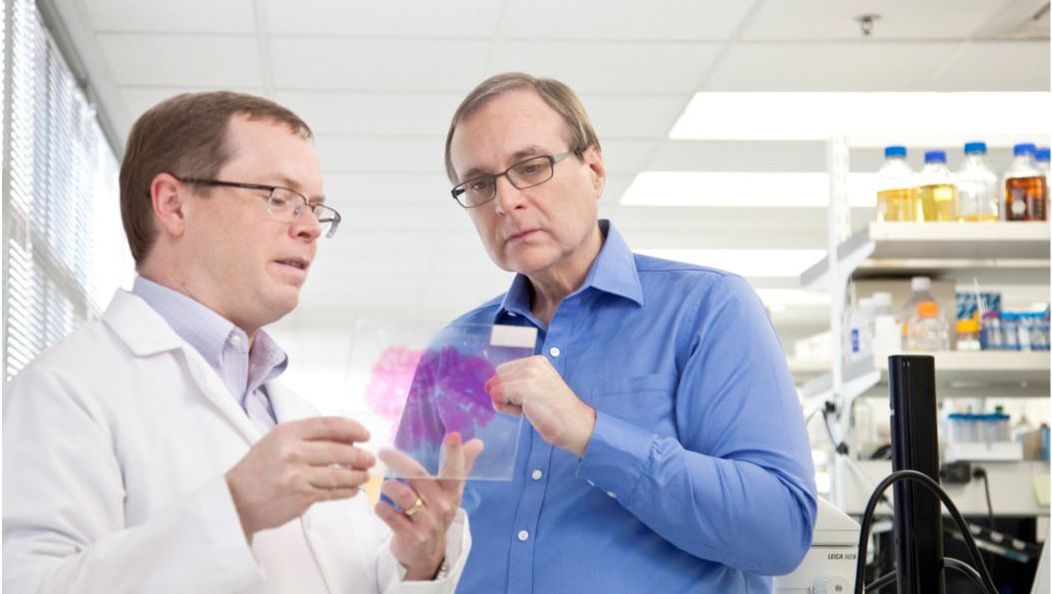

By Scarlett Brown Artificial Intelligence (AI) is increasingly becoming one of the main topics concerning the future of technology and is making its way into our daily lives even at its infancy. Just think of self-driving cars or even the phone in your pocket - just ask Siri. These examples are just the beginning, and there seems to be big plans in the works for AI... ...and one man believes it can even save the planet. Paul Allen, a scientist, innovator, philanthropist, and (dare I say) conservationist. As the co-founder of Microsoft, Paul Allen is investing in projects dedicated to science, technology, conservation, and community culture. From being the founder of Vulcan Inc., Allen Institute for Brain Science, Institute for Artificial Intelligence, Stratolaunch Systems, and many more foundations he has proven himself dedicated to using the latest technology to lead the way into a better future.

Here are a few ways Paul Allen has helped fill in these information gaps and how he is striving to make sure technology can keep up with conservation demands:

“Early work is proving that algorithms can sift through the massive amounts of data streaming back from these monitoring systems. In turn, humans and machines can begin to identify the plants, birds, fish, and other species captured by these remotely deployed cameras, microphones, and more – sometimes down to the unique individual. And we’re finding new ways to deploy these technologies every day. For example, Microsoft is working on ways to use organisms such as mosquitoes as small, self-powered data collection devices that can help us better understand an ecosystem through the animals they feed on.” - Paul Allen’s team AI can also take high quality images to create detailed geographic maps and monitoring systems to help researchers and the government assess the health and status of habitats and ecosystems over time. AI can also keep collecting more data in order to become smarter as more information is received causing a learning curve that provide us with knowledge on a much faster and needed scale.

The newest and most innovative technology could be the key to saving the planet, however it’s going to take humans themselves to help. We need the public, government officials, scientists, and conservationists to all come together to use the resources at hand to save ourselves in the end. Paul Allen has extensively contributed to conservation efforts with the use of technology and I strongly encourage you to check out his website and many other articles and posts about his projects. Because if I’m being honest, I could’ve easily written 50 more pages.

1 Comment

This post is part of our ongoing project of SMASH Reflections, authored by our inaugural class of Fellows.

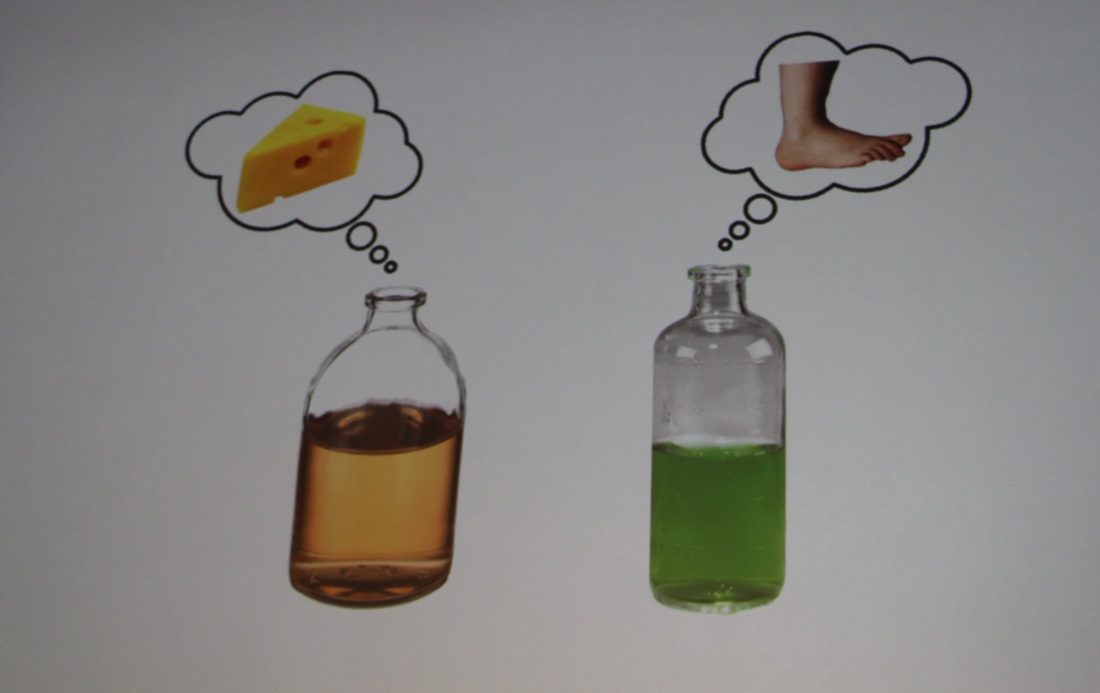

By Sophie Gomani As I listened to Nielsen’s SVP Audience Insights Peter Katsingris speak at the Science Media Awards Summit in the Hub (SMASH) last month, it was interesting to discover just how rapidly Americans are changing their viewing patterns from TV to online platforms. Today, as multimedia devices are in more than a quarter of TV households with viewers now replacing old TV models with smart TV’s, millennials are spending on average of about 10 hours connected to multimedia devices for any given day. As a youth and a journalist, I also find myself drawn to online platforms and often ask if whether growth of online channels means the beginning of the end for TV network viewing. In my country, Malawi, the TV industry is still new and the reach is very low. For several years after Malawi attained democracy in 1994, the country had only one national TV network. It was only until three years ago - when Malawi Communications Regulatory Authority started issuing TV licenses to those in the private sector - that new channels started emerged. At the moment, Malawians heavily rely on digital satellite TV channels offered by a South African based company, Multichoice. However, due high poverty levels in the country, most people cannot afford to pay for monthly subscription fees. In Malawi, the use of multimedia devices is growing, but mostly in cities and towns. The same cannot be said for those living rural areas where a majority do not own a TV and have very little access to the internet. For many Malawians, Radio remains the biggest source of information. However in America, Katsingris explain that the TV reach is still strong In fact statistics reveal that overall TV viewing in households still remains at an all- time high. The only difference is that people are now in front of the TV for fewer days. Today, individuals, organizations and companies from over the world are able easily share content and interact with global audiences through online platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Snapchat. Furthermore, the emergence of online channels such as Amazon and Netflix have also made it simple for people to access media content on their own schedules rather than abiding by TV Network programming. Even thought TV viewership is very different in Malawi compared to America, I must admit that it did not come as a shock to learn that American viewers are moving to online platforms, especially when you look at how technology has advanced over the years. What also did not surprise me is that the major shift from TV to online is happening largely among millennials ages 18 to 34, which Katsingris said is largely due to change in lifestyle, technological development and growth in digital platforms. Even network executives have openly admitted that this is indeed a challenging time for them and has forced many of them to re-define their media strategy. When it comes to science programming, DocumentaryTelevision.com's Peter Hamilton said before the online revolution, most networks had drifted away from their brands and most science programs were being replaced by character driven series. However, he said the emergence of on-demand channel like Netflix and Amazon with their big budget science documentaries and A-List talent at executive level have given a boost to Science programming. So how are Science program producers responding to the online video revolution? Well, rather than try to fight the online video revolution, most networks such as National Geographic Channel, BBC, PBS and Science Channel have started to embrace online platforms. Senior Executive Director for NOVA, Paula Aspell said she understands that young people are not watching TV programming on their TV’s, and therefore it is important for networks to try and give audiences media content on a platform that they want. “Luckily, there seems to be a real drive for science content that is really appealing to people,” she explained. However, she stressed that it is important for networks to avoid giving up what they have for the sake of online ratings; instead they need to take the time to study their mission statements and understand what their audience expects of them. Another step that networks are taking is to develop big budget science documentaries, such as the high-profile MARS series by the National Geographic Channel, with the aim of drawing in more viewers. At the pace at which technology is advancing, one cannot help but start to believe that a time may come when all media content will be accessed via online platforms. And although TV viewing still remains high in countries like America, it would only be wise for all TV producers embrace the change. About the author: Sophie is Malawian radio journalist and producer with over four years experience working in Malawi’s print and broadcasting industry. She specializes in stories and programs that focus on rural development through the promotion of sustainable agricultural innovations. She holds a Bachelor's Degree in Journalism and Media Studies obtained at the University of Malawi, The Polytechnic. This post is part of our ongoing project of SMASH Reflections, authored by our inaugural class of Fellows. by Amy Gilson If you listen to podcasts or have considered making one of your own, you may have noticed an explosion in podcast offerings over the past couple years. According to one analysis (http://bit.ly/podtrendm), the number of podcasts launched on iTunes each month went from 1,500 in 2010 to 6,000 in 2015. The audience for podcasts is growing as well. Over that same period, the percentage of Americans who listened to a podcast in the past month increased from 12% to 17%, based on a Pew Research report (come on, let’s get that number up, people!). Podcasting is in a similar phase to blogging and vlogging a couple years ago, with many amateurs and professionals stepping into the space. Along with radio shows released in podcast format, such as This American Life, several new podcast networks (PRX’s Radiotopia, Gimlet, Slate’s Panoply) support a cornucopia of high-quality podcast-native content. Amateurs with passion for a particular topic or just for chatting with friends start successful podcasts as well. All in all, there’s not much separating a person with an idea from a lucky listener’s ear buds. It’s this immediacy and intimacy that has become the stylistic hallmark of the podcast medium. However, that doesn’t mean podcasting is easy, and podcasting about science comes with its own unique challenges. I found this out as part of a team of graduate student scientists at Harvard University that launched the Sit’N Listen science podcast about a year ago. Our original idea was to make a conversational podcast, similar to Slate’s Political Gabfest, but about scientific topics in the news. We decided on egg freezing as the subject of our first episode. It seemed like a winning topic, but recording did not go well. As soon as the tape was rolling, our tongues turned to wood. We’d use a piece of scientific jargon for several minutes without realizing it. Eventually, the conversation devolved into mad Googling over the details of ovum maturation. We coped by beginning to script each episode. This brought big improvements in clarity and content, but we lost the flow that comes from natural conversation or good acting. On September 22, the Science Media Awards Summit in the Hub (SMASH) featured a panel focused on radio and podcast science media. Nathan Tobey (@natetobey, Nate Tobey Consulting) produced the panel with Ari Daniel (@mesoplodo, NOVA) as moderator and panelist Mary Harris (@marydesk, New York Public Radio), Adam Cole (@cadamole, National Public Radio), and Genevieve Sponsler (@genevievetweet, Public Radio Exchange). Here are the four things I learned from their discussion: 1. Tell a story A podcast episode doesn’t have to be over in three minutes like a YouTube video, so story can drive the episode. A story isn’t about a topic or program, it’s about a person, place or a thing. Taking this message to heart can lead to some extremely visceral episodes. To bring the experience and science of hypothermia’s onset to listeners, PRX’s Outside podcast narrated the story in second person: “At 95 degrees, you’ve entered the zone of mild hypothermia. You are now trembling violently as your body attains its maximum shivering response.” The process of doing scientific research is another source of narrative for science journalists. For example, Ari told a story about traveling to the Arctic to tag narwhals with a team of scientists. As he puts it, he’s happiest making a radio piece when he feels like he’s populating a play, so he thinks about the characters, the backdrop, the sounds… This method brings out the drama behind publically visible results, such as an article or a new medical treatment, of scientific research. While narrative leads an audience down the road of a scientific story, a complex scientific concept can be a bump in the path. In this case, metaphor is your best friend. Mary used cruise control as a metaphor to explain a glucose meter and insulin pump that worked together to maintain stable glucose levels in a diabetes patient. While you were listening to that audio segment, you were right there in the car with her. 2. Embrace the role of producer What a scientist thinks is the most interesting might not be the best for the audience, and if you’re interviewing or co-hosting with someone who isn’t used to radio, it’s your job to work with them and get a good recording, or “good tape” in radio lingo. In general, people want to sound good, so it’s okay to be upfront with what they can do differently to sound better. 3. Collaborate Science podcasts are a great opportunity for collaborations between scientists and journalists. PRX’s STEM Story Project finds new content through an open call for science, tech, engineering, and math pitches that are screened by a team of scientists and journalists. Scientists working closely with producers host some of PRX’s podcasts. This is a nice way to bring in different types of voices. 4. Be yourself Messy is okay in a podcast, and sounding stupid can make for great tape. Have a long conversation with a co-host and edit this audio together with audio from interviews. Try to sound as much like yourself as possible. It can be awkward and nobody likes hearing his or her own voice, at least at first, but there’s no need to have a great newscaster voice or to channel Ira Glass. Technical aspects of getting started The barrier to starting your own podcast is lower than ever. Even a simple smart phone can record decent sound, and free audio editing software and audio file hosting makes it an affordable hobby too. Here are some resources either mentioned during the session or that I’ve found helpful while getting into podcasting. Tools, techniques, and ideas: http://transom.org, recommended by Genevieve Beginners guide to podcasting (http://bit.ly/2cWtEEc) I’ve found this one helpful Connecting SoundCloud to iTunes and other podcast apps (http://bit.ly/2dCNwyO) Free audio editing software: Audacity (http://www.audacityteam.org/) Free sound effects (www.freesound.org) 5 science reporting pitfalls (http://bit.ly/2do9PVq) So what are we going to do with this new perspective over at Sit’N Listen? Well, I think we’ll venture into unscripted territory again and tell more stories as a tool for illuminating science. About the author: Amy Gilson (@aigilson) As a graduate student at Harvard University, Amy is working on understanding how the protein molecules encoded in our and every organism’s genomes evolve. Throughout graduate school she has been in the leadership of Science in the News, Harvard's extensive graduate student scicomm organization. Last year, Amy helped launch the podcast Sit'N Listen (http://bit.ly/sitnlist), which presents science in its social context. This post is part of our ongoing project of SMASH Reflections, authored by our inaugural class of Fellows. By Mashaal Sohail Nothing stinks but thinking makes it so. Imagine you are given a bottle with some clear orange water and told that it smells like cheese. You enjoy the smell and dwell on memories past of fine creations you have devoured in your time. You are then given another bottle, this one with green liquid and told that it smells like gym socks. Your gag reflex comes on and you retreat after a single sniff. Now, imagine I tell you that actually there is only a single chemical, isovaleric acid, a part of body odor, and that I synthesized it and added it to two different bottles of food coloring, and told you that one was feet and the other was cheese. You would probably feel deceived, but also a little confused. This experiment in “olfactory illusions” inspired scent researcher Sissel Tolaas and synthetic biologist Christina Agapakis to dig deeper into the olfactory connections between feet and cheese. How could you have a completely different experience of the smell even though the chemistry is identical? And why is the chemistry of feet so similar to that of cheese? As Agapakis and Tolaas continued to investigate, they found more and more information pointing to the microbiological similarity of the two ecosystems. Cheese smells like feet, and vice versa, because very similar bacteria are present on both. Could cheese then be made with toe bacteria? Given the differences in our response to isovaleric acid in sterile bottles, how would someone react to the smell of foot cheese? To explore, Agapakis and Tolaas sampled bacteria between the toes of themselves and of friends and colleagues (who else could they possibly ask?), cultured the microbes they found in milk, and successfully created cheese. Truly, food for thought. Looking more closely at the chemistry and biology of cheese, we can basically think of our feet as 20x concentrated cheese. While a strangely hilarious thought, it’s true that we are what we eat! For Agapakis and many others, learning truths such as these make us reflect on questions such as where is an appropriate place for bacteria to be, how do we think about cleanliness, and how to define our relationship with our microbial _________. I leave a blank there because the relationship status is, as yet, undefined. Most of us can relate to a childhood where we got yelled at by our moms for bringing germs into the home. We knew germs caused diseases and made us sick. We learned to use antibacterial soaps and products to wipe clean those germs from our clean bodies and homes. In the last few decades, we have learned from labs such as Christina’s that, on the contrary, we spend every moment of our lives with the bacteria that live within and on us, on our feet, in our guts, on our skins, in our throats. We could never become “clean” of our bacteria because then we would also be cleaned of our selves. Somehow, in our course of becoming who we are, becoming us came to mean sharing a partnership with bacteria throughout our lives, a partnership in which they share and sometimes dominate our physical beings. We just weren’t aware of it. Current research holds the number at 39 trillion bacterial cells vs. a mere 30 trillion regular old human cells in an average person. Not only this, but Agapakis’ research makes us wonder if we also share part of who we are with cheese, and what else? So that’s why we have an undefined relationship with our microbes. We have gone from one that was purely antagonistic to one where we are realizing that we have actually been working with each other and for each other for a very long time. Such realizations can enter the facts of science must faster than they can be absorbed through the collective psyche of human cultures. Now that we know, what will we make of this new knowledge? That remains to be seen. For Agapakis, it means using microbes to generate odors and sensations for us. She moved on from this research project to one of a more industrial nature. As the creative director at Ginkgo Bioworks in Boston, she looks at biology as a design problem. How did the rose get its smell? She starts with natural elements such as a rose plant, looks at its DNA sequence, and then uses genetic engineering to make microbes produce the same smell. Am I off my beaker talking about yeast smelling like a rose? No! By engineering the gene sequence from the rose plant into the yeast cell, the yeast starts encoding the molecule that makes the rose smell like a rose. Agapakis and her team can then extract the fragrance molecule from the yeast. “It’s not that easy,” she laughs, “in fact, it’s really, really hard.” She thinks of her work as building a wind tunnel for microbes. The origins of flight were really based in the origins of the wind tunnel. You had to test many different versions and see if their design is going to work. By seeking inspiration in nature, in how biology solved this chemical problem, she puts microbes to work, something we have already been doing for a very long time, just unconsciously.

About the author: Mashaal is a PhD student in Harvard University's Systems Biology program. Her doctoral research uses genetic data to study the action of natural selection on modern humans. She is interested in evolution, history and philosophy of science, and the links between biology, environment, and behavior. This post is part of our ongoing SMASH Reflections series, authored by our inaugural class of Fellows.

By Vanina Harel “What’s VR?” I asked, “and why is everyone talking about it?” Somebody turned to me and said “here, I’ll show you.” I put the headset on and was instantly transported. “I’ve always wanted to dive with whale sharks!” I shrieked. Experiential media has immense potential and can take different forms. It can be 360° video, computer-generated virtual worlds, games, augmented reality, or a combination of forms. In the context of science, it provides a new opportunity to engage and inspire. So, what is the potential of experiential media and how can we use it in science communication? Here are a few takeaways from the September 20th session. How is it different from other forms of media?

How can we use it?

So, why aren’t we all using yet? Anthony Geffen compares the current state of VR to the early days of the iPod: “We had a cool new technology but no music to download for it.” VR is still new and we are still figuring out the rules, but the opportunities are limitless. In 5 to 10 years, we may all have a VR headset at home, at school, and at work. We are not there yet, but immersive storytelling is definitely a new opportunity for powerful science communication and education, and we should embrace it. About the author: Vanina Harel is a National Geographic Young Explorer and a filmmaker. She has travelled to South Africa and Botswana to produce a short film about rhinoceros conservation, co-produced Chesapeake Villages, a 30-minute documentary that aired on Maryland Public Television, and recently completed a 22-minute documentary film about lagoon conservation in Mauritius.

This post is part of our ongoing project of SMASH Reflections, authored by our inaugural class of Fellows.

by Alie Caldwell SMASH16 was a whirlwind kaleidoscope of science and media. In the course of three days, I had so many conversations, thoughts, and emotions about science, communication, and the future, that it's going to take some time for me to break it all down and figure out exactly what to do with it. As a young neuroscientist and a YouTube creator, I was particularly interested in observing and understanding the ways that traditional science film production methods are colliding and changing with the advent of online digital media--how new platforms and formats are radically adjusting the way we consume content, and even more importantly, who is now able to access and use that content. I had hoped that the closing keynote, in which Marco Werman interviewed Stephen Pinker and Richard Wrangham, would help me synthesize some of the information I'd been cramming into my brain all week. After all, the description for the event said that they would be discussing the use of media for violence and peacemaking, and thinking about what the future holds. It seemed like a good way to wrap up a week that had revolved around the changes in our world and our media landscape--a chance to consider the future and how we could use what we'd discussed in our work. I was honored to have the chance to hear from such brilliant academics. But I was surprised to find that the content of their conversation didn't provoke much introspection. The key message was an optimistic one: We are, as a species and society, living in the safest and most prosperous era of history that humankind has ever experienced. By the numbers, this is true; as a species, we have continued on an overall upward trend toward increased equality and economic stability. What I found interesting (and ultimately a bit disappointing) about this message, was that it didn't really encourage the audience to think critically about the future. The message that I got was "Things are pretty great for humans, so don't worry too much about it." Even if that's true, it doesn't give me--or our society--a reason to grow and change. Our era may be the best in human history, but we can still want things to be better. We can have the lowest disease rates ever and still want to hunt for cures. I was also struck by the disconnect between the attitudes of Drs. Pinker and Wrangham and those of some of the international attendees. To be blunt, it is easy to say that “the numbers” show that the world is doing wonderfully when you yourself are unlikely to be affected by racism, sexism, poverty, or war. Dr. Pinker commented that he doesn't count systemic violence as "violence" in the traditional sense. And he is right that systemic violence is more subtle and difficult to measure. But these kinds of violence can still kill, and there is still a great deal of work to be done in this arena, both in our own neighborhoods and on a global scale. Similarly, I found it interesting that the speakers' optimism stemmed from the statistics. Over the course of the week, a key takeaway has been that the Deficit Model--assuming that if your audience just had more information, they would understand and believe the “facts”-- is incorrect. This is why we still have anti-vaccination advocacy groups and climate change denial, despite the deluge of public conversations and information on such topics. Empathy for the audience is a crucial component of effective science communication; we, as communicators, need to understand the motivations and fears of the people we are trying to reach. For those of us in the audience on Thursday, the statistics showing that the earth is prosperous were comforting, but I don't think they would inspire much confidence in someone struggling through war or famine. This particular point is why I find new digital media to be so fascinating--it has so much potential. These new platforms are not just a shift that we as creators need to “survive”. We need to embrace the change, and use it to blow up the traditional concept of science media. These are the tools of the digital era: users can choose how, where, and when to consume information, letting us reach new audiences in exciting new ways. To me, these platforms represent empowerment for the learner, giving them more freedom in how they learn. The onus is on us as creators to adapt and grow with the radically changing face of media. We need to think critically about how we can increase access and engagement with people who may be science curious, but lack the access that is readily available to traditionally educated populations. I don’t have the solutions, but there is a growing chorus of diverse voices who have some ideas. In the end, Marco Werman’s conversation with Dr. Stephen Pinker and Dr. Richard Wrangham didn’t look too far into the future. I can understand why. Digital media is progressing so rapidly that it’s hard to keep up with every platform and style. It’s impossible to know where we’re going, or how we’re going to get there. But I know we’re in for an exciting ride, and I’m glad to be a part of the changing face of science media. For more of my thoughts on SMASH16 and this particular point, please check out the video I’ve shared on Neuro Transmissions about the event: About the author: Alie is a graduate student of neuroscience at UC San Diego, where she works with Dr. Nicola Allen to understand the roles of brain cells called astrocytes in the growth and development of the brain. She is the writer and host of Neuro Transmissions, an educational YouTube channel making the brain accessible to everyone. This post is part of our ongoing series of SMASH Reflections, authored by our inaugural class of Fellows.

By Adam Haar Horowitz SMASH was wonderful. The Science Media Awards and Summit in the Hub lasted the whole week of 9/19 and focused on science communication. Science storytelling is complex, nuanced, crucial: I applied as a Fellow to SMASH16 because brain science—teasing apart these universal experiences like empathy, attention, memory—is by necessity a science that takes first person perspective as data, and as such a science that benefits from active inclusion of everyone’s subjective reality in the conversation. A diverse dialogue is not only morally right, it is essential to gathering quality brain data. It’s an open question as to whether a synesthete or a seasoned neuroscientist knows more about synesthesia, and that’s pretty cool. 1st-3rd Person Because of this necessary diversity of perspective—this diversity of experiential truths—throughout SMASH I reflected on an important personal truth: If I want to take a stand for anything as a scientist, as a person, it’s that curiosity should be as important a part of my neuroscience “toolkit” as objective knowledge or technical skills. If you back away from that notion of first-person perspective as data for a minute, you realize that it’s quite wild. Neuroscience offers this bridge between the objective and subjective, this great equalizer between subject and scientist, between body-as-data and scientist as data collector. So when I went to SMASH, it was with the intention of creating media that would encourage non-scientists to have unembarrassed engagement with neuroscientists. In a sense, I want to open doors to neuroscience labs around the country for people with some curiosity between their ears. Curiosity People who are curious about sleep can go to Harvard’s division of Sleep Neuroscience, and someone like Dr. J. Allan Hobson there will actually care about your lucid dream story. The same can be said if those of you with insight into fluctuations in happiness send Dan Gilbert an email. And that’s not true of chemistry, or physics—as a ‘lay-person’ (that term, ever a wall between experts and non-experts, a binary I’ll take a crack at in another post) you’d have nothing much to offer in those labs. At best, you might be given a link to a MOOC to go learn more. And neuroscience is such a young field, with yawning white space to be filled! Conclusions about the brain are regularly turned entirely on their heads—even at times by just one case study. So my interest in creating neuroscience media is not so much about spreading capital T Truth, but more about spreading breadcrumbs, curiosity, and insight into the stuff of the self, so that those who are uninitiated and feel unwelcome might be excited enough to engage and send the field for a tumble or two. Scientists Taking A Stand I sat down to write about a panel I watched called Scientists Taking A Stand, but had to start with where I was coming from. I heard some wonderful career scientists like Sean B. Carroll and Chris Filardi on this panel quote Asimov saying “the saddest thing about society is that science is producing new knowledge way faster than society is gaining wisdom.” And I understand that science produces knowledge, which I value immensely and commit myself to daily. But I also recognize that knowledge is not wisdom. That the thing creating that gap may not simply be a lack of more knowledge, that often problems like climate change or attacks on neurodiversity are as much about bending cultural spectrums as they are about battles waged between legions of the ‘ignorant’ and the ‘educated'. Later in the SMASH16 programming, Dan Kahan, of Yale’s Cultural Cognition Project, told all of us that scientific facts don’t change policy to save the environment or get homosexuality taken out of the DSM 4; media that works to change perspectives of voters and takes the task of engaging opposed perspectives seriously does. That the distinguishing factor between those who would, and would not engage with viewpoints opposed to their own was level of curiosity, not level of information. So, if I can take a stand for anything at the moment, it’s that. It’s inquisitiveness, it’s the opportunity to initiate a conversation. Because in my work as a fledgling scientist—if I even can be called one this early on in my career—I’ve already seen that experts can be truly damaging if they impart knowledge upon non-experts as an objective authority on how those non-experts’ bodies and brains work. Do it wrong, and you are suddenly assuming ownership, forcing labels, devaluing layperson perspectives, making subjects feel like objects. Young Neuro(scientist) I recognize, of course, that neuroscience is different than ecology, that facts exist and are crucially important. But the second piece I heard on stage from the panelists (who were eloquent and wonderful, let me say) was that I should wait until a few years after my post-doc before I engaged in Science Storytelling, so I could be sure of what I said and not upset any higher-ups. In my mind that hierarchical, peer-review based form of communication so common in science is patently anti-curiosity. And it seems so strange in the world of neuroscience, where facts are ever-shifting and space to be explored far outweighs space explored, to suggest that I’ll ever ‘know what I’m talking about,’ that there will be a moment where I’m sure my knowledge is wisdom and it must be shared and sharing it won’t offend anyone. All in all, I feel comfortable taking a scientific stand for curiosity like wildfire and an open dialogue, but not much else. It may be that neuroscience is simply too young for the imparting wisdom game. It may be that I am. About the author: Adam Haar Horowitz is a neuroscience Teaching Assistant at MIT’s McGovern Institute exploring mindfulness, meditation, and mind-wandering. He has always loved playing the role of translator from experiential to empirical and connecting personal stories to scientific inquiry. Adam is fascinated by what it means to be human—micro and macro—and by what advancing this understanding can mean for the future of self, communication, and community. This post is part of our ongoing project of SMASH Reflections, authored by our inaugural class of Fellows. By Alex Albanese Looking for ways to build up your science communication skills? Here are some tips from the SMASH16 session “Breaking Science: In the News” with David Ropeik (@dropeik) and Deborah Blum (@deborahblum), moderated by Miles O'Brien (@milesobrien). 1) Don't write a science story, write a good story about science. Make your story undeniably irresistible! Miles O’Brien recalls his early days at CNN in 1991 when a TV producer watched his segment on buckyballs (when 60 carbon atoms organize themselves into a sphere) and proclaimed "I already knew about buckyballs, but that was actually interesting!" Some science stories tend to be more appealing to the general public at their core: space exploration, robots, gene editing, etc. However, it's up to you to find the most interesting aspect of each story. The best storyline might come from the science itself, the implications of the discovery, the people behind the work or from other sources. If your story is relevant or relatable, it is possible to transcend the "science news section" and reach a broader audience. Remember: good storytelling taps into a reader's emotions and interests. 2) Find teachable moments. Current events in news and pop culture offer opportunities to reach the general public. David Ropeik suggests, "If a forest fire ravages an area, write compelling stories about how fire works. When an airplane crashes, write a story explaining the science behind a crash investigation.” The current events on everyone's mind present a golden opportunity to reach those without scientific training. Recently, a picture of a striped dress went viral because it sparked a massive debate whether it was white-gold or blue-black. As the debate raged on between the white-gold and blue-black camps, several articles popped up to discuss the science behind the optical illusion. Having a good sense of pop culture and what's on people's mind will help frame your story in the most compelling context. 3) Gaze into the crystal ball. How can you know what's on people's mind? Social media! Timing is everything when trying to reach a large audience. Be sure to use Twitter and other social media to spot growing news stories. Is the scientific community divided or excited? How is the general public responding to the news? Is there a misunderstanding, excitement, or ethical concerns? The initial reactions of both specialists and non-specialists can help identify a better narrative for your story. Sometimes the original story is less interesting than the debate it creates. 4) Use your superpower! As a journalist or scientist, you have an area of expertise. Use it to its full advantage! it will allow you to find teachable moments and write your best stories. Is the media getting a story wrong? Is the general public developing an irrational fear? Journalism used to require journalists to remain invisible. However, this is changing as the lines between personal blogs and journalism blur. And if you are not an expert, there are many resources at your disposal, such as social media. Are there vocal experts that stand out? Don’t be afraid of reaching out to other experts who can help you out. (Just make sure to vet them first, especially if you are relying on discussions that take place on social media!) 5) Make the most of your format. Science news can be covered by Tweets, TV series, and everything in between. Short form can be the most difficult to write without resorting to sensationalism. The 25 Commandments for Journalists states that the first sentence is the most important sentence you will ever write. But those second, third, and fourth sentences are important, too. A reader will drop your story at the first prospect of boredom. Ropeik said that he regrets "the harm he caused" writing short pieces that intentionally played up the aspects of a story that would get the most attention. The competition for audiences is fierce, and the impulse to capitalize on what is “sexy” or controversial is hard to avoid. According to Ropeik, long-form is the antidote. In longer pieces, you can paint the full picture of story, address misconceptions, and reset the narrative. Unfortunately, there are smaller audiences for long-form journalism. This is where the art of seduction comes into play. You can take advantage of the scarcity principle and provide access to exclusive information. A longer news story can reach a large audience if it provides new information to an ongoing story. Long form can also seduce its readers through style. Deborah Blum wrote The Poisoner's Handbook, in which the history and science of modern forensics is presented with the flair of a thriller novel. Ultimately, you can be successful in short- or long-form pieces, as long as you recognize the constraints of your chosen format. Correction: An earlier version of this article misidentified David Ropeik and Miles O’Brien. About the author: Alex was born in Montreal and obtained his BSc and MSc in microbiology and immunology at McGill University. He completed his PhD at the University of Toronto investigating nanoparticle-tumor interactions. He is currently completing his postdoctoral studies at MIT growing and imaging stem cell ‘mini-brains’. Alex is also the creator of Focal Point (University of Toronto) and GLiMPSE (MIT) podcasts where scientists chat about their journey, work, and outlook. Artificial intelligence: The idea of “thinking machines” discussed at SMASH16 sparked interest, excitement, and denial around the world. This post is part of our ongoing SMASH Reflections series, authored by our inaugural class of Fellows. By Israel Bionyi The 2016 Science and Media Awards Summit in the Hub (SMASH16) celebrated the best works of science in media, highlighting the need to effectively communicate science and creating synergies between the scientific community and the media world. Big science stories, trends in science media, insights around science topics relevant to food, evolution, astrophysics, biodiversity, forensics, big data, neuroscience, and sound were discussed in a variety of panels. A keynote by Joi Ito, director of MIT Media Lab on Tuesday, 20 September 2016, moderated by Paula Apsell Senior Executive Producer at NOVA, discussed the potential of disruptive technologies in shaping the future of societies, including artificial intelligence and bitcoin. Ito discussed two types of Artificial Intelligence (AI): artificial general intelligence (AGI), a machine system that could successfully perform any intellectual task a human being can, and specialized AI, often called machine learning, which appears in self-driving cars, the algorithms of Facebook and Google, and predictive policing. “My focus is specialized learning, things like machines assisting judges determining bail and things like driverless cars,” Ito said. “AI or any kind of machine learning system isn’t programmed. What happens is that an algorithm is created and trained with data, much more like raising a kid.” But do we need thinking machines or automated things that act like humans and could control certain aspects of our lives? On the streets of Boston, Uber drivers are terrified by the idea of driverless cars. Christopher Obazee, 35, from Nigeria, makes $4,000 a week from Uber as a full-timer. His colleague, Mohammed, 55, from Morocco, makes $60 a night as a part-timer. Both Uber drivers worry that they will not be able to provide for their families both in the US and back in Africa if driverless cars take away their jobs. “I have heard about AI before, and the idea that we are going to have automated cars really scares me, because it is going to put many people out of jobs,” said Mohammed. However, Ito’s argument during the keynote focused more on quality of work and safety. “If you spent enough money building a driverless car kind of quality like Google has in the streets and you eliminate humans driving cars, it would be much safer today,” Ito stated. In all, whether linguists, scientists, researchers, businesses or philosophers, people from same industries often have divergent interests on AI and equally opposing concerns. At the heart of the Netherlands in the city of Ede, located directly between the large cities of Utrecht and Arnhem in the province of Gelderland, a social worker, Annemieke Eshuis, was exposed to Ito’s prospect of AI through machines and robots that played key medical roles, such as “huggable robots” in hospitals and doctors’ “consulting robots”. “If you start putting robots around patients as doctors and social workers, I really feel we are going the wrong way,” said Eshuis. “The purpose of life is to love and to be loved, to have intimate relationships. We need trust from two sides to build a relationship; a robot doesn't have a heart, so you cannot have real communication with a robot. As a social worker, I see that people want to share their heart’s feelings. They want to sense that you are listening to them; they can feel that in their hearts if you really do.” In rural towns and villages of Cameroon, rural chiefs and natives reacted to the concept of AI. Nehemiah Yumoh, a native of Bangolan (found in the Northwestern part of Cameroon) who now resides in Germany, said this technology is out of place in the African context. Like many chiefs interviewed about AI, Yumoh will fight it with his last bone, because otherwise “the value and place of man will disappear,” he said. “Besides, robots are strange to an African man and I think something like that is certainly not welcome in Bangolan”. But Janis Sacco, Director of exhibitions at Harvard Museums of Science and Culture, sees the potential for AI to help preserve African cultures and heritage. She believes that documenting, digitalizing, and archiving historical traditions and practices in machine learning systems could prevent them from disappearing. Whether we agree with AI or not, machine learning systems is a reality today and it is proving effective to ensure safety and productivity. Despite risks, research and development on AI is continually advancing and we are going to learn to have a world where we trust robots to perform certain tasks. Further resources View Joi Ito’s keynote on Facebook About the author: Israel Bionyi is a freelance reporter, communications specialist, and environmental blogger specializing in climate change, water, energy, forests, and wildlife conservation. He founded the blog ‘The Wink Writes’ and contributes to Fairplanet magazine and Cameroon’s Standard Tribune. He is also Assistant Editor for the Society for Conservation Biology’s African Conservation Telegraph and a member of the International League of Conservation Writers. Stay connected Following SMASH on Twitter, #sciencemedia, and Facebook.

This post is part of our ongoing project of SMASH Reflections, authored by our inaugural class of Fellows.

By Rodrigo Pérez Ortega  Joe Hanson from "It’s Okay to Be Smart" and Dianna Cowern from "Physics Girl" joined forces and made a video in both YouTube channel. Photo: "It’s Okay to Be Smart." Joe Hanson from "It’s Okay to Be Smart" and Dianna Cowern from "Physics Girl" joined forces and made a video in both YouTube channel. Photo: "It’s Okay to Be Smart."

Did you hear that last Radiolab show? Did you watch the last episode of MinutePhysics? What about the shark photo from NatGeo on Instagram? From YouTube channels to tweets and Facebook pages, science is now everywhere in the digital world, and science communication has found its niche in this ever-changing landscape. YouTubers, podcasters and bloggers have emerged, each with a very personal touch to their content. With nearly one-third of the world population using social media, creating engaging content for such wide and dynamic audience is especially hard. A key feature of digital and social media is that the production costs are quite low and the reach is high. New platforms and trends are always emerging, and we have to constantly adapt to them if we want to reach more people. During the SMASH 2016, a special session tackled the challenges and peculiarities of creating compelling content in different digital platforms. Anna Rothschild, host of Gross Science, moderated the discussion among the panelists: Joe Hanson, host of It’s Okay to Be Smart, Erin Chapman, host of the Shelf Life series, and James Williams, VP of Digital Video at National Geographic Partners. What did we learn from this interesting discussion? Here are the 5 most important things you have to take into consideration if you want to go viral. 1. KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE AND BE LOYAL Now, more than ever, science communication is about establishing a personal relationship with the viewer/ listener/ reader, connecting with your audience on a deep level. And so, one of the best things about social media is that you get to know them pretty well. With every platform and app, you can get instant statistics and feedback. You can track the age group, the male to female ratio, watch time, etc. of your audience and use this information to shape your content, get more shares and views, and present the science in a more meaningful way. “Going viral” is especially hard, because the competition is fierce and the online audience is quite demanding. As Joe Hanson says: “they have a high bulls**t filter”. So come up with a compelling story and make it authentic. And deliver on any promise you make to your audience. 2. CHOOSE THE RIGHT PLATFORM There are more than 50 social media platforms these days, some more popular than others. And there’s a reason for it: they’re all different, and so are their audiences. YouTube is video and animation, Instagram is pure photo and some video without audio, on Facebook you can throw some text, but visuals are definitely key. So, you have to find the right platform for your content. Always have a story and don’t try to push your content from one platform to another if it doesn't fit the format. For some platforms you have to keep it short, while in others long format is better. For some, you have to start with the punchline in order to hook your audience. What works well in Snapchat might not work in Facebook, so be wise. Also, don't worry about mastering all the platforms. Stick to what works for you and embrace it. 3. FAIL! AND LEARN Please fail. That's the best way to learn what works and what doesn't. And your audience will let you know. “We’re just bouncing off of failures until we find our focus. We need the failures” says Williams. And you know what's the best part? As Hanson puts it, "if it fails in the internet, nobody sees it". Sounds like a good deal. 4. COLLAB. COLLAB. COLLAB. In every platform, there are subgroups, small communities that are interested in similar things. And even if it's all science, the audiences can be quite different. So contact fellow science communicators and invite them to do something together. You don't have to be in the same physical space. Great things can come out of a collaboration. 5. BE BRAVE AND EXPERIMENT! Remember that there are no rules in the internet, so it's a playground for creativity. It has an amazing built-in democracy. Don’t be afraid to try new things and use your platform to its maximum potential. An Instagram documentary? Sure! “It doesn’t matter what the medium is, what matters is the truth and the story” says Erin Chapman. Getting out of your comfort zone and putting yourself out there might be hard at first, but it’s worth it. Some things might not work, but hey, remember point 3? Perhaps your goal might be to educate and entertain, to make science fun. But always think big, because after all the effort, the payoff can be quite surprising. For example, Hanson was once contacted by somebody in Iran asking how to download one of his videos because the bandwidth was not the best and he/she wanted to share it because it was important content for an Iranian audience. Champan’s series, Shelf Life, has accomplished a good male to female ratio of viewers. Achieving gender balance is difficult in science communication reach, let alone science itself. Thanks to one of Chapman’s videos, an entomologist from Singapore reached out and initiated a collaboration with a laboratory at her institution. Williams recounts that the week Finding Dory came out, his team launched a campaign to raise awareness about the danger of buying tang fishes, which are taken from the wild. It went viral and had a big impact—they were literally “saving Dory”. So, always take the extent and power of the internet into account. And remember to always take different languages and ethnicities into consideration, since you might be making a bigger difference than you think. Note: Appropriately for a panel on social media, this session was transmitted live on Facebook. You can watch it here. About the author: Rodrigo is finishing his degree in Biomedical Science at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Mexico City. He is passionate about neuroscience, research and science journalism. For the past couple of years, he has been a contributor at TecReview, Medscape en Español, ¿cómo ves? and others as a freelance science writer. His work has been published both in English and Spanish and he works continuously to raise awareness about the science and scientific journalism made in Latin America. |

AuthorAs the curators of the Science Media Awards Summit in the Hub (SMASH), we believe storytelling is a common thread in our shared human experience, and that new media allows us to convey the wonders of scientific discovery in new and compelling ways. Archives

October 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed